The evolution of cooking technology offers a remarkably clear view of how innovations layer rather than replace, each finding its niche rather than destroying what came before. And it provides an unexpectedly apt framework for understanding how AI is currently integrating into our work and lives.

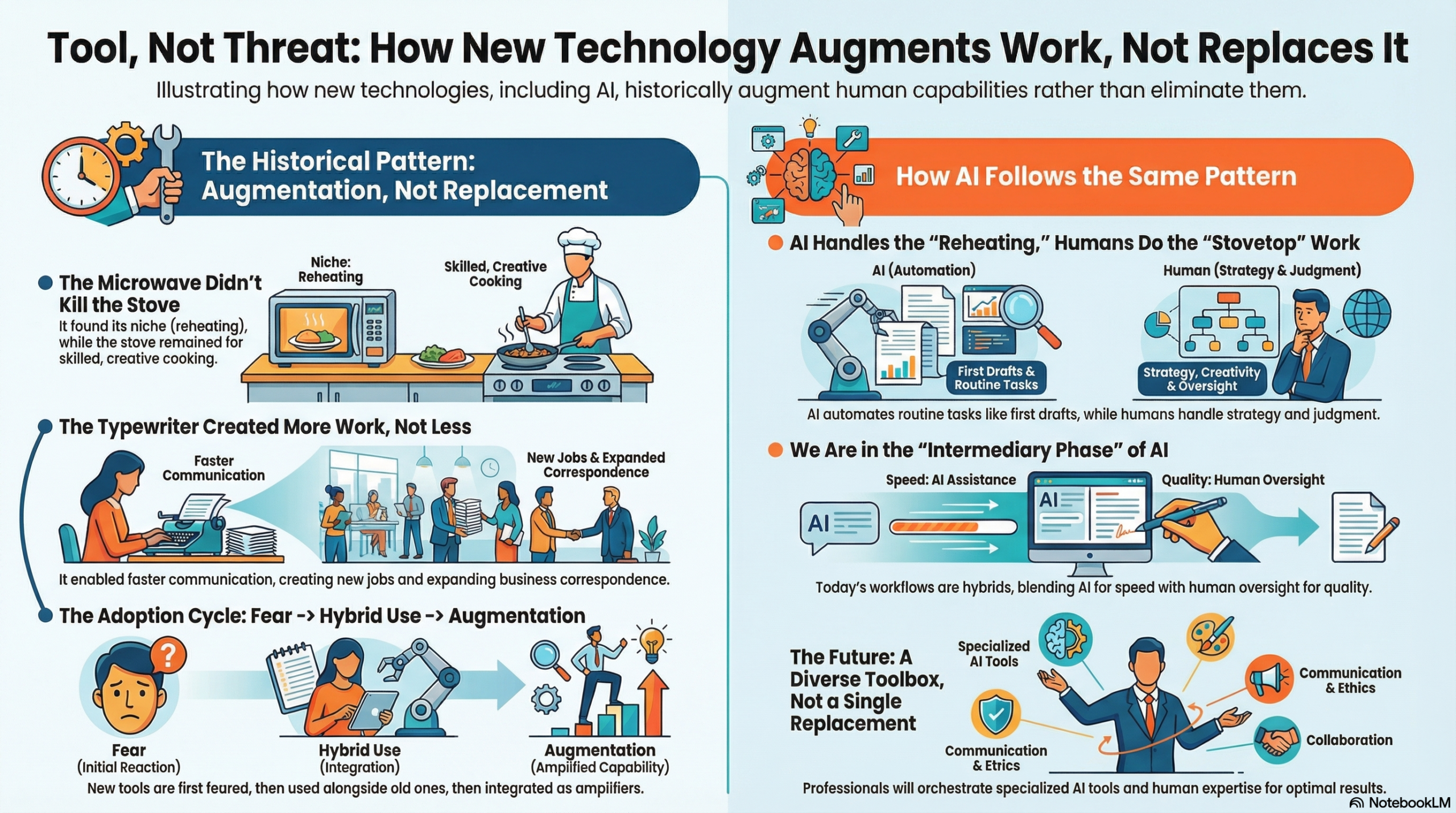

Consider the microwave’s arrival in homes during the 1970s. Critics worried it would make stovetops obsolete and end “real cooking.” Instead, it carved out its own territory: reheating leftovers, melting butter, steaming vegetables in minutes. The stovetop remained essential for searing meat, simmering sauces, achieving the Maillard reaction that creates complex flavors. Each tool excels at different tasks.

This mirrors how AI is finding its place in workflows today. AI doesn’t replace the developer. It handles boilerplate code generation, suggests completions, and catches common errors while the developer focuses on architecture, logic, and creative problem-solving. Just as the microwave didn’t eliminate the need for cooking skill, AI coding assistants don’t eliminate the need for programming expertise. They handle the repetitive “reheating” tasks while humans do the sophisticated “stovetop work” that requires judgment, creativity, and deep understanding.

The slow cooker didn’t replace the Dutch oven. It freed people to work all day while dinner cooked unattended, solving the specific problem of “I need dinner ready when I get home but can’t be here to monitor it.” Similarly, AI is automating the unattended workflows: summarizing meeting transcripts, monitoring systems for anomalies, generating first drafts of routine reports. The human still makes the critical decisions (what to cook, which insights matter, how to refine the output) but the tool handles the time-consuming background work.

The air fryer created a new capability rather than replacing existing tools. It gave health-conscious cooks crispy textures with less oil and faster preheating, but didn’t eliminate deep fryers or ovens. Each found its niche. AI translation tools follow this pattern perfectly. Professional translators haven’t disappeared. Instead, AI handles rough translations of straightforward content while human translators focus on nuanced work: literary translation, legal documents, marketing copy that requires cultural adaptation. The AI expanded access to basic translation while elevating the human translator’s role toward more sophisticated challenges.

This pattern of technological adoption through augmentation rather than replacement extends powerfully across workplace history. The typewriter transformed office work in the late 1800s, but it didn’t eliminate writers or reduce writing jobs. Instead, it accelerated documentation, enabled carbon copies, and actually created vast new categories of work. The role of “typist” emerged as a profession. Business correspondence expanded because it became faster and more legible.

AI is following this exact trajectory. Customer service hasn’t been eliminated. It’s been stratified. AI chatbots handle the “What are your hours?” and “Reset my password” queries that consumed enormous human time, while customer service representatives focus on complex problems requiring empathy, judgment, and creative solutions. The total volume of customer interactions has actually increased because AI made basic support economically viable at scale. Just as typewriters created more writing work by making it accessible, AI is creating more interaction capacity by making routine interactions efficient.

When word processors arrived in the 1970s and early 1980s, they didn’t immediately sweep typewriters away. For years, offices ran both. Word processors excelled at revision, letting writers edit without retyping entire pages. But typewriters remained faster for quick notes, forms, and labels. The transition period saw dedicated word processing machines like the Wang and IBM Displaywriter, occupying a middle ground before affordable personal computers with word processing software became standard.

We’re in this intermediary phase with AI right now. Content teams use AI to generate first drafts but heavily edit them. Designers use AI to explore concepts rapidly but refine them manually. Lawyers use AI to review contracts for standard clauses but apply human judgment to negotiations and strategy. These aren’t fully automated workflows. They’re hybrid processes where AI handles specific substeps while humans maintain control and apply expertise to the parts that matter most.

The dot matrix printer phase illustrates this intermediary technology phenomenon perfectly. These noisy, slow printers were the bridge between typewriters and modern laser printers. They weren’t ideal, but they solved the immediate problem: getting digital documents onto paper affordably. Offices kept typewriters for envelopes and forms while using dot matrix printers for longer documents.

Current AI tools occupy a similar transitional space. They’re imperfect. Prone to errors, requiring verification, sometimes producing unusable output. Yet they solve immediate problems: generating variations, processing large volumes of data, providing starting points. Teams develop hybrid workflows: AI generates options, humans select and refine. AI analyzes data patterns, humans interpret significance. AI drafts responses, humans add judgment and personality. These workflows aren’t the final form, but they’re solving real problems today while we learn how to use these tools effectively.

This pattern reveals something crucial about technological fear and adoption. Initial resistance stems from focusing on what might be lost rather than what could be gained. When typewriters emerged, concerns about penmanship degradation and the loss of personal correspondence character were real and loudly voiced. Yet typewriters didn’t destroy writing. They democratized it, accelerated it, and created entirely new forms of written communication.

The anxiety around AI echoes these historical fears with remarkable precision. “AI will eliminate creative work.” “AI will make us intellectually lazy.” “AI will homogenize content.” Each concern contains a kernel of truth while missing the larger picture. Yes, AI changes the nature of work, but so did every previous tool. The question isn’t whether change happens, but what new capabilities emerge and what new challenges become accessible to human effort.

People become dependent on new technologies not because they’re forced to, but because the tools genuinely improve their capability or efficiency in specific contexts. No one mourns the hours spent retyping documents to correct errors. The word processor eliminated that drudgery, and writers redirected that time toward revision, refinement, and additional writing.

AI is demonstrating this same property in real time. The writer who uses AI to generate headline variations doesn’t miss manually brainstorming fifty options. They redirect that energy toward evaluating which resonates, refining the winner, and crafting the actual content. The analyst who uses AI to clean and standardize messy datasets doesn’t miss the tedium. They invest that saved time in deeper analysis and insight generation. The researcher who uses AI to synthesize papers doesn’t miss skimming hundreds of abstracts. They focus on critical evaluation and novel synthesis.

The kitchen technology evolution shows this even more clearly because it’s personally tangible. Anyone who’s used a microwave to defrost meat while simultaneously sautéing vegetables on the stovetop while bread toasts understands that multiple technologies working in concert expand capability. The fear that microwaves would end “real cooking” proved unfounded because they serve fundamentally different purposes.

This is precisely how AI integrates into workflows. A marketing team might use AI to generate campaign concepts, human creativity to select and refine the direction, AI to produce variations and test copy, human judgment to optimize based on brand voice and strategy, AI to analyze performance data, and human insight to extract strategic lessons. Each tool (human and AI) handles what it does best. The result isn’t replacement but orchestration, much like using multiple kitchen appliances simultaneously to prepare a complex meal faster than any single tool could manage.

What makes people eventually embrace new technology after initial resistance is the lived experience of enhanced capability. The typist who feared word processors discovered that revision became creative play rather than tedious retyping. The cook who thought microwaves were inferior found them indispensable for specific tasks while continuing to use traditional methods for others.

We’re witnessing this transformation with AI in real time. The designer who initially resisted AI image tools as “cheating” now uses them to rapidly explore compositional options before creating the final work manually. The programmer who dismissed AI code completion as unreliable now can’t imagine developing without it for handling imports, boilerplate, and common patterns. The researcher who viewed AI summarization skeptically now uses it routinely for initial document triage while reading critical sources carefully.

The trajectory consistently moves toward tool diversity rather than monolithic replacement. Modern offices contain computers, printers, scanners, phones, video conferencing systems, and yes, sometimes still typewriters for specific forms. Modern kitchens accumulate appliances because each genuinely solves particular problems better than alternatives.

The AI landscape is evolving this way too. We’re not heading toward a single AI that does everything, but toward specialized AI tools for specific tasks: one for code, another for writing, another for image generation, another for data analysis, another for research synthesis. These tools coexist with traditional software, human expertise, and collaborative workflows. The professional of the near future won’t choose between human capability and AI. They’ll orchestrate both, selecting the right tool for each aspect of their work.

This understanding becomes especially relevant as we face new technological waves. The pattern suggests that resistance often stems from imagining complete replacement when actual adoption creates complementary ecosystems. The technology that survives isn’t always the “best” in absolute terms, but the one that finds its sustainable niche, solving specific problems more effectively than alternatives while coexisting with other tools.

AI is finding these niches rapidly. In legal work: contract review but not strategy. In medicine: image analysis but not patient care. In education: personalized practice but not mentorship. In creative work: variation generation but not artistic direction. Each application builds on AI’s genuine strengths (pattern recognition, rapid iteration, tireless consistency) while preserving the human elements that require judgment, empathy, creativity, and contextual understanding.

The historical pattern offers comfort. We’ve navigated these transitions repeatedly. The anxiety is normal, the adjustment period real, but the outcome typically involves expanded capability rather than diminished humanity. We gain new tools without fully abandoning useful old ones, and we discover applications we couldn’t have imagined before the technology existed.

The typewriter didn’t just make writing faster. It enabled businesses to scale communication in ways that created entirely new organizational structures. The word processor didn’t just simplify editing. It made iterative refinement so easy that writing quality expectations fundamentally shifted. The microwave didn’t just reheat food. It changed meal planning, family schedules, and food product development.

AI won’t just make existing tasks faster. It’s already enabling individuals to accomplish what once required teams, small businesses to deliver what once required enterprise resources, and rapid experimentation that once required prohibitive time investments. A single entrepreneur can now test dozens of marketing approaches, analyze competitive landscapes, generate professional graphics, and draft comprehensive content. Tasks that previously required hiring specialists or spending weeks of focused effort.

The concern that AI will eliminate jobs misses the historical lesson: new tools change what jobs look like and create new categories of work we couldn’t previously imagine. The typist role emerged with typewriters. The “administrative assistant” evolved from typist as word processors made typing universal but administrative coordination became more valuable. The “social media manager” couldn’t have existed before social platforms. The “data scientist” emerged when data analysis tools made working with large datasets feasible.

AI is already creating new roles: prompt engineers, AI trainers, AI ethicists, AI integration specialists. But more importantly, it’s shifting existing roles toward higher-value activities. The customer service representative becomes a complex problem solver and customer advocate. The paralegal becomes a legal strategist and client counselor. The junior analyst becomes an insight synthesizer and strategic advisor. The routine parts of these jobs get automated, but the work doesn’t disappear. It evolves toward the parts that require distinctly human capabilities.

The most interesting pattern from kitchen technology applies here too: we often don’t know the most valuable applications until people start experimenting. The microwave was initially marketed as a time-saver for full meal preparation, but its killer application turned out to be reheating and convenience foods. The slow cooker’s original pitch emphasized budget cuts of meat, but it became indispensable for busy families’ scheduling needs.

AI’s most transformative applications likely aren’t the obvious ones we’re discussing today. Yes, it helps with writing, coding, image generation, and data analysis. But the truly revolutionary uses might emerge from unexpected combinations and creative applications we can’t yet imagine. Someone will figure out how to use AI for something we didn’t anticipate, just as creative cooks discovered you could make mug cakes in the microwave or use slow cookers for fermentation.

The key insight from a century of technological adoption: tools are neither saviors nor threats, but amplifiers of human intention and capability. The typewriter amplified communication capacity. The word processor amplified revision capability. The microwave amplified convenience. AI amplifies analytical capability, creative iteration, and execution speed.

The professionals who thrive aren’t those who resist the tools or those who blindly adopt them, but those who thoughtfully integrate them into workflows while maintaining the human judgment, creativity, and expertise that tools can’t replicate. Just as the best cooks use microwaves without abandoning fundamental cooking knowledge, the best knowledge workers will use AI without abandoning critical thinking, domain expertise, and creative insight.

We’re in the early, awkward phase. The dot matrix printer era of AI, if you will. The tools are imperfect, the workflows are being figured out, and the integration feels clunky. But look at any well-equipped kitchen or modern office, and you see the endpoint: a rich ecosystem of complementary tools, each excellent at specific tasks, orchestrated by humans who understand both the tools’ capabilities and their own irreplaceable value.

The revolution isn’t that AI replaces human work. The revolution is that AI handles the routine, repetitive, and time-consuming elements, freeing human capacity for the sophisticated, creative, and meaningful work that only humans can do. Just as the microwave didn’t end cooking but freed cooks to spend their time on more interesting culinary challenges, AI won’t end knowledge work. It will elevate it.